The Gigue is Down

At the start of the Choir’s year of Passion rehearsals in January, 2006, I made the following broad statement: “Everything Bach composed was either a dance or a chorale (hymn) or both.” (Ed: All truths are generalizations, including this.)

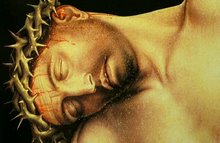

About two months ago in the New York Times appeared a review of the ‘Carnegie Hall Choral Workshop’ the most recent of a series founded in 1990 by Robert Shaw and continuing. The Bach ‘St. Matthew Passion’ was the subject of January’s five-day session, directed by the world-renowned conductor and Bach specialist Helmut Rilling. The 76 participants, selected by grilling audition, are choral professionals and talented amateurs. In his New York Times review James Ostereich quotes Maestro Rilling as stating something to the effect that Bach always composed dances. OK so far. His example in the St. Matthew is the final bass aria “Mach dich, mein Herze, rein” which he says is a gigue. What!! A jig?? A giga?!?!? In whatever language, it’s a jig. You know, right after the soloist’s introductory recitativo, “At evening, hour of rest . . . ends the Savior’s pain . . comes the dove again with an olive leaf in her bill . . . so cool and still . . . His body rests in peace . . . O precious thought to ponder.!” Then Mary Mother, Mary Magdalene, Joseph of Arimithea, and assorted Roman soldiers jump up and down in a spirited jig around the bottom of the cross with Jesus hanging limp above them, while the bass sings his aria, “Make thyself pure, my heart, where I will entomb Jesus . . . there to sweet rest betake Thee.”

It is a dance, no question; it’s a pastorale, a lullaby. In all truth, it’s the most peaceful moment in the entire Passion which by now has known three hours of lament, bloodshed and breast-beating anguish. Hello?